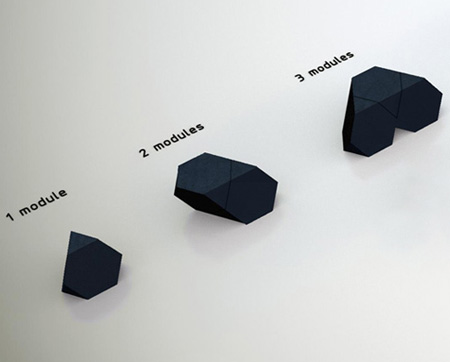

模块

The old way

传统JavaScript有相当多的模块化方案(AMD,CommonJS,UMD等)。大体都是通过一个外部函数返回一个携带各种闭包的对象,达到将公用的API暴露出来的目的。类似这样

之所以会诞生出这么多方案,无疑是需求跑在了前面,而语法不直接支持这些。于是乎ES6吸收了一些C系语言的思想,直接支持模块化。

Before the new way

在具体介绍语法之前,来看看ES6模块化和以往有何不同

ES6模块化是基于文件的,一个文件只能有一个模块;

ES6 modules are file-based, meaning one module per file. At this time, there is no standardized way of combining multiple modules into a single file.(ES6模块化是基于文件的,意味着每一个文件只有一个模块。与此同时,没有一个将多个模块合并在同一个文件内的标准化的方式)

ES6模块化是单例的;

Every time you import that module into another module, you get a reference to the one centralized instance. If you want to be able to produce multiple module instances, your module will need to provide some sort of factory to do it.(每次引用一个模块,实际上只是获取了一个中心实例的引用。如果你想生成多个模块实例,你的模块需要提供某种工厂模式来实现)

The new way

exports & import

一个模块包含多个独立的子功能,如果需要公开相应的功能模块,直接用export关键字即可,来看一个例子:

导入模块

export default

ES6完全支持

import语句从历史项目AMD或CommonJS模块化方案中导入模块。

来看代码

两者几乎等价,这意味着export输出模块本质上和CommonJS模块化方案没什么区别,ES6完全可以从历史代码引入模块,减少代码迁移的痛苦。

循环依赖

A依赖B,B依赖A,怎么做到不出问题呢?

《You Don’t Know JS ES6》书中给出了一个例子:

我们来试想一下,foo和bar两个函数在同一个函数作用域内,运行起来自然是没问题的,然而在模块化环境下,ES6则需要做一些额外的工作才能使得如此循环依赖生效。但是,怎么做到呢?

In essence, the mutual imports, along with the static verification that’s done to validate both import statements, virtually composes the two separate module scopes (via the bindings), such that foo(..) can call bar(..) and vice versa. This is symmetric to if they had originally been declared in the same scope.

大概意思是本质来说,实际上这样的循环依赖将两个模块(A和B)的函数作用域虚拟地联合在了一起,如此一来foo可以调用bar,bar也可以调用foo。这和将foo和bar两个函数声明在同一个函数作用域的实际效果是一样的。

模块对象 & 聚合模块

使用import *实际上导出的是模块命名空间对象,将所有模块的属性全部导出。

聚合模块又是什么呢?很好理解,将其他细小模块整理起来,在同一个模块里聚合,并导出。类似于先import…from了模块,然后再将其export,这样的操作无非就是把两步合成一步来做。

Classes 类

墙裂声明:此类非彼类,JavaScript中的Classes和其他语言Classes虽然类似,但有本质的区别,而JS中所谓的Classes只不过是语法糖。

实现原理

At the heart of the new ES6 class mechanism is the class keyword, which identifies a block where the contents define the members of a function’s prototype.(class机制核心在于class关键字,这标识了一个定义了函数原型上面的成员的语句块)

有点拗口,直接来个例子:

可以这么说,你所看到的class的内容,实际上就是该函数的原型对象(Prototype Object)本身。

我们趁机来复习一下JavaScript的Prototype和Constructor吧。

每一个函数都包含一个prototype属性,这个属性是指向一个对象的引用,这个对象称之为“原型对象”(prototype object)。每一个函数包含不同的原型对象。当将函数用作构造函数的时候,新创建的对象会从原型对象上继承属性。

在JavaScript中,类的实现是基于其原型继承机制的。如果两个实例都从同一个原型对象上继承了属性,我们说他们是同一个类的实例。

如果两个对象继承自同一个原型,往往意味着(但不是绝对)他们是由同一个构造函数创建并初始化的

构造函数是用来初始化新创建的对象的。使用new调用构造函数会自动创建一个新对象,因此构造函数本身只需初始化这个新对象的状态即可。调用构造函数的一个重要特征是,构造函数的prototye属性被用作新对象的原型。这意味着通过同一个构造函数创建的所有对象都继承自一个相同的对象,因此他们是同一个类的成员。

—引自《大犀牛》

认真看看下面的Demo

所以我们很清楚,ES6所谓的Classes特性只是在ES5基础上做了美化,用贴近其他语言语法(Java)的形式,模拟出其他语言有的面向对象的特性(继承,多态,封装),使得代码看起来更加明确易懂。

extends & super

接着上面的Foo Bar例子

仔细想想,在pre-ES6的时代,要模拟面向对象是一件很蛋疼的事情。首先我们熟知面向对象三个重要特征,继承、多态、封装。尤其是继承,传统的做法都是通过父类将原型对象赋值给子类原型对象实现的,与此同时还要注意,在原型对象赋值以后,需要更正子类原型对象中的构造方法,blabla…特别啰嗦。ES6这次索性把以上我们说的一整套流程固定成了几个语法糖,在明确语义的同时,减少了重复啰嗦的代码实现。

再来看一组代码对照,一切都会很清晰了。

new.target & static

老规矩,先看代码

Be careful not to get confused that static members are on the class’s prototype chain. They’re actually on the dual/parallel chain between the function constructors.(静态成员并不在类的原型链里,而是存在于两个函数间的构造方法内)

如上所说,离开了构造方法,使用new.target是无效的。

模块化编程部分暂时介绍到这里,如果遇到什么没介绍到的,我会及时补充进来。